Gardeners are voracious beasts. They are always angling for more: more plants, more pockets of earth in which to ground them, more trees, more sunshine, grander views, larger expanses. What’s behind the clipped hedges and the carefully cultivated drifts of blossoms, beneath the soft shade of oaks and maples, lies a gardener’s true heart—acquisitive, rapacious, curious, passionate, searching, ruthless. The quest never ends—for a rare specimen, for a variant on the familiar, for a plant that will yield new delights, for a bosky glade that will enchant, for the ideal spot for entertaining, for a more perfect world.

In that sense, Thomas O’Brien is a true gardener. The renowned designer who crafted a distinctive merging of classic English comfort with an industrial edge has launched a multitude of projects and products over the past three decades—not to mention a host of imitators, none of whom has managed to capture his mix of retro charm, all-American ease, and masculine clarity. His shop Aero, with its inimitable mix of his own designs and global finds from around the world, has been a Manhattan design destination, in all its various locations, since 1992. And five years ago, he and his husband, interior designer Dan Fink, opened the charming Copper Beech, a source for funky vintage country finds, high style and gourmet provisions in Bellport, Long Island, where they maintain their second home and extensive gardens.

O’Brien purchased what had been a former school for boys, affectionately called the Academy, more than 20 years ago, long before Bellport became a sought-after retreat among the chic set. “The house was so run-down,” he remembers. “But even then, you could see it had great potential. The lines were elegant, and there were central doors in every elevation. The place had wonderful white pines and cedars, and a lot of nearly dead maples, which we removed.” A major highlight was the property’s more-than-300-year-old copper beech tree. “You can see the very top of it from the bay,” O’Brien says proudly. “It was here long before these houses were even thought of. Dan and I were married under that tree.”

He initially established three gardens. The first was the lush and flower-filled portico garden parallel to the Academy’s living room and sunroom. The more structured kitchen garden was planted by the garage, with beds of herbs and flowers delineated by low boxwood hedges. “The kitchen garden always gives me the feeling that it is the safest place on earth,” O’Brien says. “It’s a mix of loose and formal. And we use the herbs constantly. There is thyme everywhere—but there’s never enough parsley,” he adds with a laugh. The third major introduction was the pool behind the house, and its adjacent topiary garden. “We wanted a vintage Hollywood-style pool with simple coping. We very deliberately made the pool the same size as the living room at the Academy,” he says. “And I have always loved Terence Conran’s topiary garden—I had a photo of it hanging over my desk for years.”

Then came a major opportunity for growth. The 1950s ranch house on the property next door went on the market, and soon plans for what would eventually be called the Library started percolating. The original house was torn down and a new guest house with offices for both O’Brien and Fink designed and built—a white-painted, black-shuttered neo-Colonial that looks as if it has always been there. O’Brien chronicled the project in his 2018 book Thomas O’Brien: Library House (Abrams), writing, “It started with the dream of a garden, then expanded to the dream of a house.”

The acquisition allowed for a greatly expanded garden, and the beloved copper beech would now be sited smack in the center of the newly conjoined three-acre property. Behind the Library, O’Brien installed a sunken garden, perpendicular to the house and surrounded by a low stone wall. “The property is so flat, I really wanted a sunken garden to add variety,” he explains. Beyond is a charming garden house he designed, fitted with a wood-fired oven, and a patio perfect for al fresco meals. The walled garden beyond was inspired by the English and European gardens he so admired. “There is a local town rule that you can’t build a freestanding brick wall,” he admits, but managed to resolve that dilemma when the wall, complete with a moon window, became the support for a new greenhouse—which allowed for yet more plants. “What I love is the hunt,” he says. “I am always checking out different garden centers.”

Like the best gardeners, O’Brien is equally passionate about high and low, subtle ground covers and majestic trees. As he leads a tour of the property, the names of special plants spill forth, a list that seems to go on and on. His design inspirations are nearly as extensive, from Russell Page to Monet’s Giverny (reflected in the lush beds, and especially the nasturtiums planted throughout) to Nancy Lancaster’s Virginia garden (which inspired the brick walkways) to his grandparents’ garden in Hamilton, New York, which he visited every weekend when he was young: “They let me create my own little garden within theirs, which I filled with trillium and wildflowers.” The memory remains vivid. “A path off the pool is lined with peonies from my grandmother’s garden,” he points out.

The parameters of the garden seem set, at least for the moment, but that doesn’t mean that there won’t be more plants, and more changes. “We plan to put in a larger vegetable garden,” he says, “even though we have a lot as it is. And we have a daunting amount of rabbits.” (That explains the newly installed rabbit fence that O’Brien designed himself.) “And I am not feeling too fond of squirrels at the moment,” he admits with a smile. He also understands the importance of subtraction as well. “I am ruthless with pruning,” he jokes. “It is a wonderful thing. It makes plants happy.” The locusts that line the brick path leading to the sunken garden are pruned high, creating a light-filled airy canopy, an ideal spot for tea or a summer lunch. The paving itself incorporates a series of low steps. “You feel it more than you see it,” he says. “And water in any downpour flows into the sunken garden.”

O’Brien knows he is a man obsessed. “From trees to bulbs to roses and vines, I love them all, small and large,” he says. “The best thing about my office in the Library House is that it gives a view of the whole garden. It looks right onto the center, and the copper beech. I wanted to create a special place, a garden that was both romantic and rustic yet formal, too. A garden that is specifically American. I think my grandmother would be proud of me.”

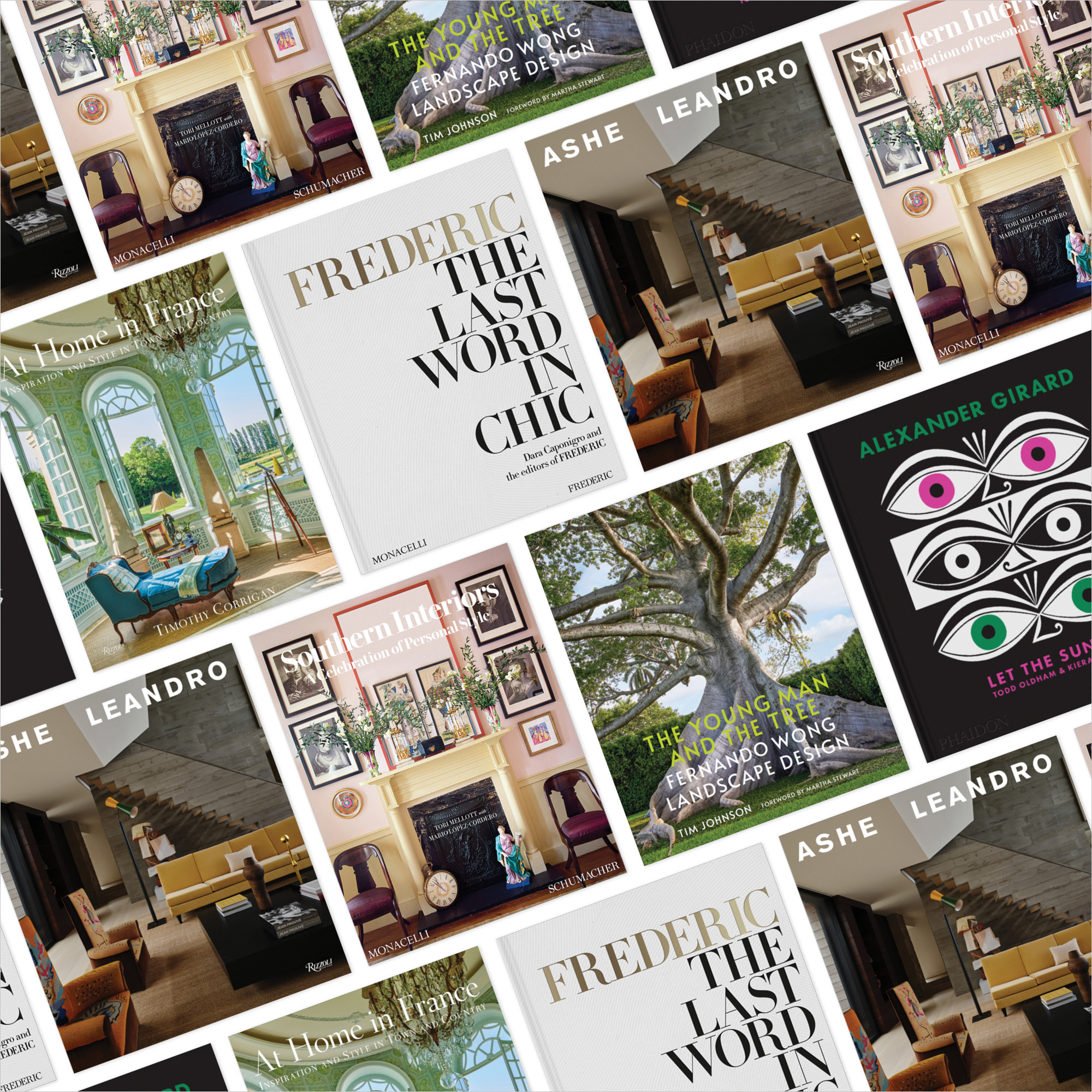

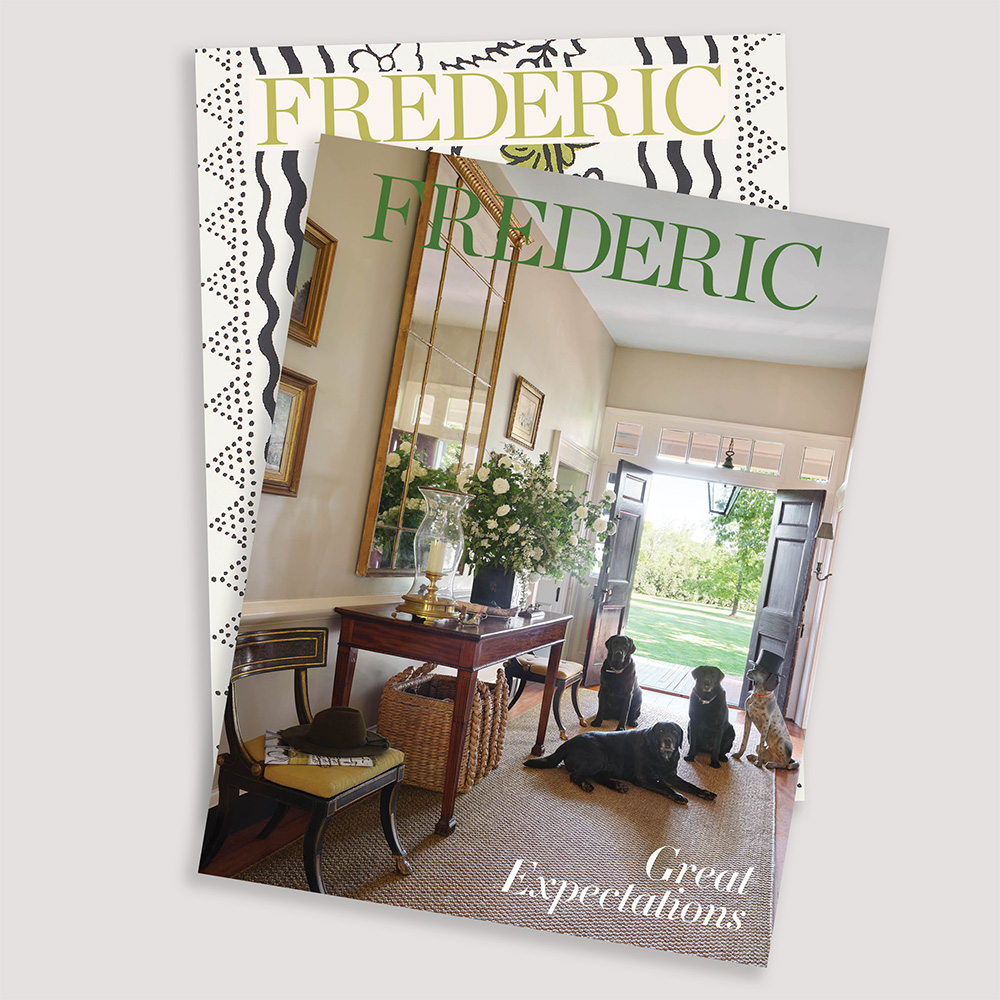

This story originally appeared in the Fall 2021 issue of Frederic. Click here to subscribe!

Gardeners are voracious beasts. They are always angling for more: more plants, more pockets of earth in which to ground them, more trees, more sunshine, grander views, larger expanses. What’s behind the clipped hedges and the carefully cultivated drifts of blossoms, beneath the soft shade of oaks and maples, lies a gardener’s true heart—acquisitive, rapacious, curious, passionate, searching, ruthless. The quest never ends—for a rare specimen, for a variant on the familiar, for a plant that will yield new delights, for a bosky glade that will enchant, for the ideal spot for entertaining, for a more perfect world.

In that sense, Thomas O’Brien is a true gardener. The renowned designer who crafted a distinctive merging of classic English comfort with an industrial edge has launched a multitude of projects and products over the past three decades—not to mention a host of imitators, none of whom has managed to capture his mix of retro charm, all-American ease, and masculine clarity. His shop Aero, with its inimitable mix of his own designs and global finds from around the world, has been a Manhattan design destination, in all its various locations, since 1992. And five years ago, he and his husband, interior designer Dan Fink, opened the charming Copper Beech, a source for funky vintage country finds, high style and gourmet provisions in Bellport, Long Island, where they maintain their second home and extensive gardens.

O’Brien purchased what had been a former school for boys, affectionately called the Academy, more than 20 years ago, long before Bellport became a sought-after retreat among the chic set. “The house was so run-down,” he remembers. “But even then, you could see it had great potential. The lines were elegant, and there were central doors in every elevation. The place had wonderful white pines and cedars, and a lot of nearly dead maples, which we removed.” A major highlight was the property’s more-than-300-year-old copper beech tree. “You can see the very top of it from the bay,” O’Brien says proudly. “It was here long before these houses were even thought of. Dan and I were married under that tree.”

-

The allée of locust trees between the garage and the Library House creates a glorious, airy canopy for a casual lunch. Cushions in Persian Lancers fabric by Schumacher.

Max Kim-Bee -

An antique suzani serves as a tablecloth, atop which is a mix of 1920s Tiffany cobalt plates and 19th-century Japon blue-and-white faience by Creil et Montereau—the same pattern that Claude Monet used at Giverny, and which O’Brien has collected piece by piece; the roses are from the portico garden.

Max Kim-Bee

He initially established three gardens. The first was the lush and flower-filled portico garden parallel to the Academy’s living room and sunroom. The more structured kitchen garden was planted by the garage, with beds of herbs and flowers delineated by low boxwood hedges. “The kitchen garden always gives me the feeling that it is the safest place on earth,” O’Brien says. “It’s a mix of loose and formal. And we use the herbs constantly. There is thyme everywhere—but there’s never enough parsley,” he adds with a laugh. The third major introduction was the pool behind the house, and its adjacent topiary garden. “We wanted a vintage Hollywood-style pool with simple coping. We very deliberately made the pool the same size as the living room at the Academy,” he says. “And I have always loved Terence Conran’s topiary garden—I had a photo of it hanging over my desk for years.”

Then came a major opportunity for growth. The 1950s ranch house on the property next door went on the market, and soon plans for what would eventually be called the Library started percolating. The original house was torn down and a new guest house with offices for both O’Brien and Fink designed and built—a white-painted, black-shuttered neo-Colonial that looks as if it has always been there. O’Brien chronicled the project in his 2018 book Thomas O’Brien: Library House (Abrams), writing, “It started with the dream of a garden, then expanded to the dream of a house.”

The acquisition allowed for a greatly expanded garden, and the beloved copper beech would now be sited smack in the center of the newly conjoined three-acre property. Behind the Library, O’Brien installed a sunken garden, perpendicular to the house and surrounded by a low stone wall. “The property is so flat, I really wanted a sunken garden to add variety,” he explains. Beyond is a charming garden house he designed, fitted with a wood-fired oven, and a patio perfect for al fresco meals. The walled garden beyond was inspired by the English and European gardens he so admired. “There is a local town rule that you can’t build a freestanding brick wall,” he admits, but managed to resolve that dilemma when the wall, complete with a moon window, became the support for a new greenhouse—which allowed for yet more plants. “What I love is the hunt,” he says. “I am always checking out different garden centers.”

Like the best gardeners, O’Brien is equally passionate about high and low, subtle ground covers and majestic trees. As he leads a tour of the property, the names of special plants spill forth, a list that seems to go on and on. His design inspirations are nearly as extensive, from Russell Page to Monet’s Giverny (reflected in the lush beds, and especially the nasturtiums planted throughout) to Nancy Lancaster’s Virginia garden (which inspired the brick walkways) to his grandparents’ garden in Hamilton, New York, which he visited every weekend when he was young: “They let me create my own little garden within theirs, which I filled with trillium and wildflowers.” The memory remains vivid. “A path off the pool is lined with peonies from my grandmother’s garden,” he points out.

The parameters of the garden seem set, at least for the moment, but that doesn’t mean that there won’t be more plants, and more changes. “We plan to put in a larger vegetable garden,” he says, “even though we have a lot as it is. And we have a daunting amount of rabbits.” (That explains the newly installed rabbit fence that O’Brien designed himself.) “And I am not feeling too fond of squirrels at the moment,” he admits with a smile. He also understands the importance of subtraction as well. “I am ruthless with pruning,” he jokes. “It is a wonderful thing. It makes plants happy.” The locusts that line the brick path leading to the sunken garden are pruned high, creating a light-filled airy canopy, an ideal spot for tea or a summer lunch. The paving itself incorporates a series of low steps. “You feel it more than you see it,” he says. “And water in any downpour flows into the sunken garden.”

O’Brien knows he is a man obsessed. “From trees to bulbs to roses and vines, I love them all, small and large,” he says. “The best thing about my office in the Library House is that it gives a view of the whole garden. It looks right onto the center, and the copper beech. I wanted to create a special place, a garden that was both romantic and rustic yet formal, too. A garden that is specifically American. I think my grandmother would be proud of me.”

See More of Thomas O’Brien’s Garden

This story originally appeared in the Fall 2021 issue of Frederic. Click here to subscribe!