In the 1930s, while American floral designers and garden club ladies were enthralled by the rule-bound, minimal aesthetic of Japanese ikebana, Irish-born florist Constance Spry was throwing out every preconceived notion of what a floral display could be. Drawing inspiration as much from vegetable patches and roadside flora as from 17th-century Dutch floral paintings, Spry combined things like catkins, kale leaves, tomato vines, desiccated grasses, lichen-covered branches, and even weeds with more conventional floral fare in an entirely original way. Her refined, high-low approach to “doing the flowers,” as she called it, forever altered how most of us approach floral arranging, whether or not we know her name.

Even among die-hard Spry aficionados, few know that—for a short time, at least—she had a floral shop in New York City. While her work had been embraced by the British aristocracy, it wasn’t until she did the flowers for the Duke and Duchess of Windsor’s wedding, in 1937, that forward-looking American society hostesses took notice. Two of them convinced Spry to let them bankroll a flower shop in Manhattan.

Shop assistants at Constance Spry's shop on South Audley Street in London, June 1947.

George Konig/Keystone Features/Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesThe space at 52 East 54th Street, which opened the following year, was as original, chic, and idiosyncratic as one would expect from Spry. A notice about its opening in the New York Times described “white as the decoration motif throughout.” The monochrome design proved a wonderful foil for the displays of flowers that graced the floors, niches, cabinets, and pedestals. The architect Harold Sterner, who had done Helena Rubinstein’s Fifth Avenue beauty emporium, designed curving walls upholstered in a thickly stuffed-and-tufted white fabric— it looked as if a chesterfield sofa had cut loose and spread itself across the perimeter—and accented them with nubby white curtains and pelmets. The dramatic lighting included a recessed checkerboard ceiling panel and a large aluminum-clad pillar with fluorescent strips running from a circular pedestal at its base and extending up through the ceiling. For furnishings, Spry chose white rattan seating and tables from her friend Syrie Maugham’s shop.

Spry wraps a bouquet in her shop.

George Konig/Keystone Features/Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesSpry sent staff over from her London shop to train her employees in New York, and even amid the Great Depression, the business flourished. But it couldn’t survive the outbreak of World War II: The operation suffered without the close direction of Spry, who was unable to travel to America, and eventually shuttered. The London outpost, however, thrived until Spry’s passing in 1960. Even today, her legacy looms large in the world of floriculture—and in the beguiling fragrance of one of her friend David Austin’s most famous English roses, the ‘Constance Spry.’

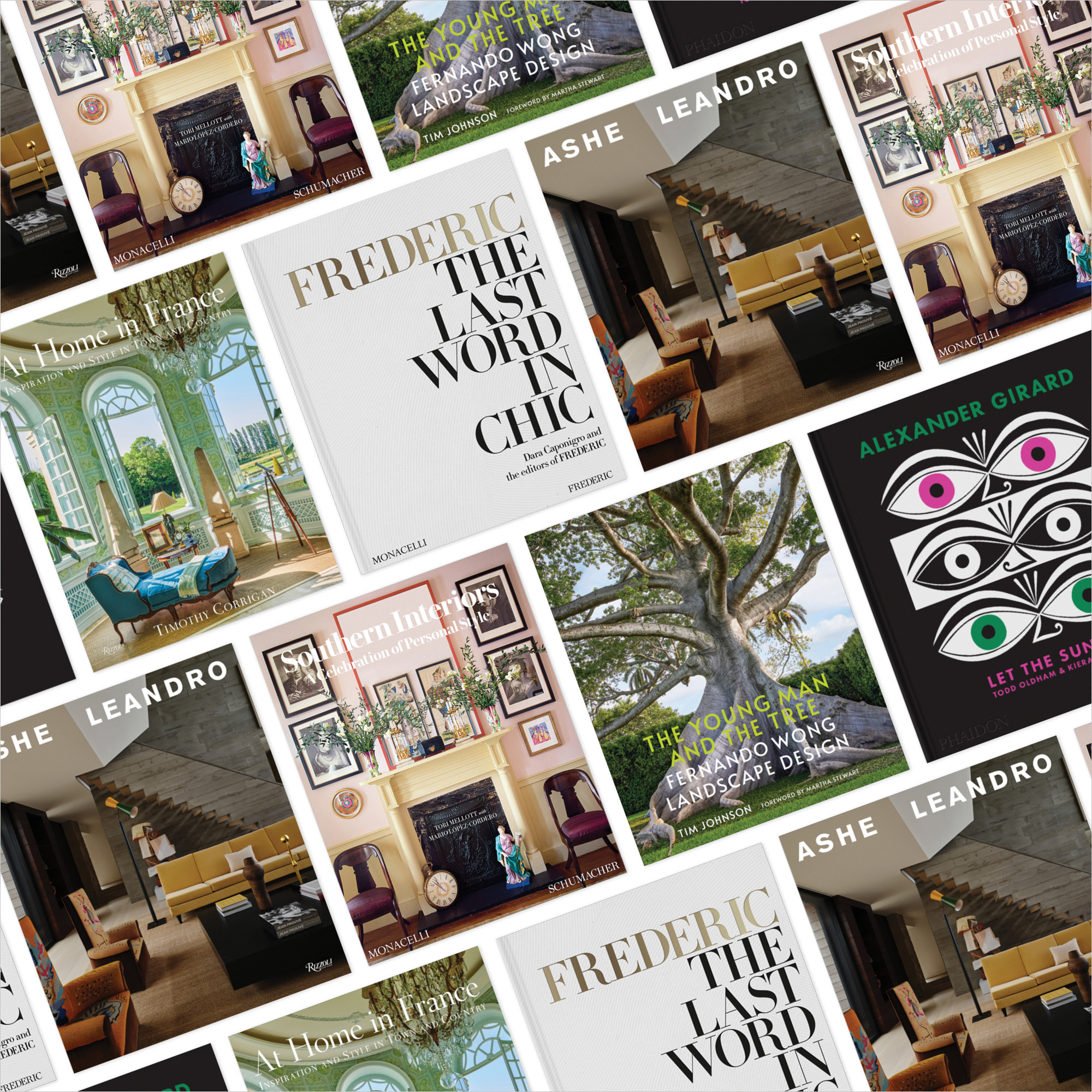

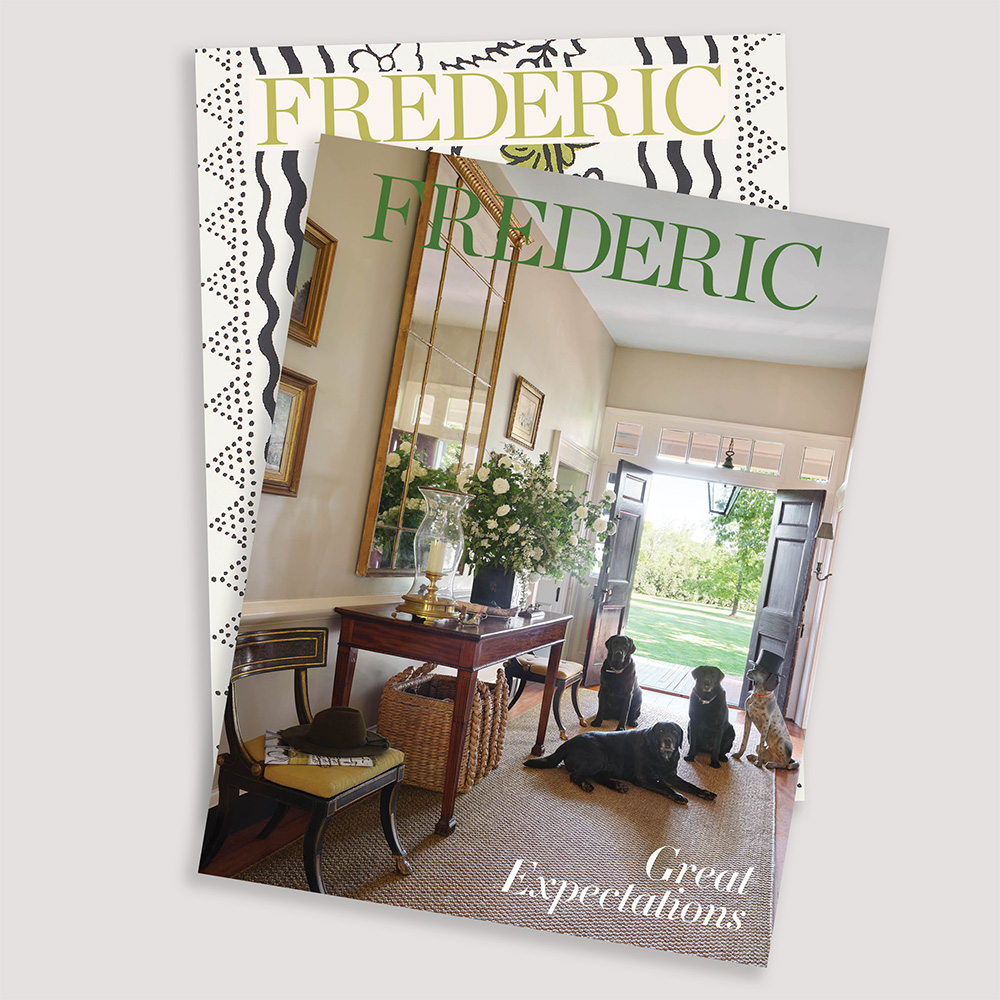

THIS ARTICLE ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN VOLUME 14 OF FREDERIC MAGAZINE. CLICK HERE TO SUBSCRIBE!