In 1973, French and American fashion faced off in a battle royale at Versailles. Five French designers, including Yves Saint Laurent and Hubert de Givenchy, sent out looks that showcased the storied skills of their ateliers, exemplifying understated chic. Then the Americans took the stage. Thirty-six models (and Liza Minnelli) strutted and sashayed down the runway in slinky gowns and pared-down sportswear by Oscar de la Renta, Bill Blass, and Halston. A new ideal of modernity took hold, an American version in which comfort and ease were primary, and attitude and insouciance were as important as craftsmanship and luxury. Suddenly, everything that came before seemed fuddy-duddy.

Ward Bennett had precisely the same impact on the American home and office. The interior and product designer took the strict geometry, hard edges, and sharp angles of the Bauhaus and International Styles, and infused them with a relaxed, sexy attitude, merging simplicity with sensuality, and updating modernism for a new era.

Bennett stripped away the classical detailing of Gianni and Marella Agnelli’s living room in a Roman palazzo to showcase the couple’s artworks, including number paintings by Robert Indiana and a work by Oskar Schlemmer that hangs over a 17th-century Italian console.

KAREN RADKAI, VOGUE, ©CONDÉ NASTBennett’s work was never about making a statement but rather serving his clients, whether he was designing office furniture for Brickel Associates, sterling-silver ashtrays for Tiffany & Co., or interiors for high-profile figures like David Rockefeller, Rolling Stone editor Jann Wenner, and Marella and Gianni Agnelli. (At a housewarming party at the Agnellis’ Rome apartment in the spring of 1970, couturier Hubert de Givenchy whispered to his fellow designer Federico Forquet, “This is the only contemporary house I have seen that has true grandeur.”) The homes he designed were minimal yet sensuous, and above all, livable. Light and shadow were always active presences. His own beach house in East Hampton is emblematic: small yet powerful with wide openings to the landscape and the sea, its foursquare geometry softened by the natural materials of aged redwood, stone, and tile.

The Hamptons house Bennett built for himself in 1968 and filled with furniture of his own design. Shades could be drawn across the massive skylight to mitigate the strong sun.

PETER AARON/OTTOBennett started working at age 13, when he dropped out of school and took a job delivering fabrics in New York’s Garment District; soon, he was creating window displays for department stores. In the mid-1930s, still in his teens, he headed to Europe to study painting. But it was furniture and interiors that ultimately allowed the fullest expression of his talents.

He was fortunate to be active at a time when many firms were embracing design as a way to showcase their values. Over his career, he designed numerous corporate headquarters (including the offices for Chase Manhattan Bank) as well as more than 100 chairs for homes, offices, lobbies, and restaurants, all as comfortable as they were attractive—Bennett himself

suffered from back pain. His range extended to textiles, tableware, flatware, and glassware.

A corner of the primary bedroom of a house in Amagansett, New York, that Bennett designed in 1970, then revamped in 1991 for Jann and Jane Wenner.

Adrian GautThough often considered a forerunner of the industrial-chic style that became so popular in the 1970s—“Stainless steel is the precious metal of our time,” he pronounced—Bennett never aligned himself with any aesthetic or movement. By the time he died in 2003, his reputation was on the wane, in part because his designs had become so ubiquitous. Decorator Joe D’Urso, who started as Bennett’s assistant before embarking on his own illustrious career, said of his mentor, “The culture has absorbed his ideas, and many people don’t even realize it. He saw no boundaries and felt he could design everything from a house to a rocket ship.

Bennett’s designs were quintessentially modern: “I expose the structure of everything I design, even of my chairs,” he once said. But in every project or piece, there is also something—an expanse of richly figured wood, the nubby texture of cane, the play of gleaming metal against honed marble, a gentle curve that envelops the back—that seduces the body, the hand, and the eye. That makes his work quintessentially American, and particularly appealing right now as a new generation rediscovers his legacy.

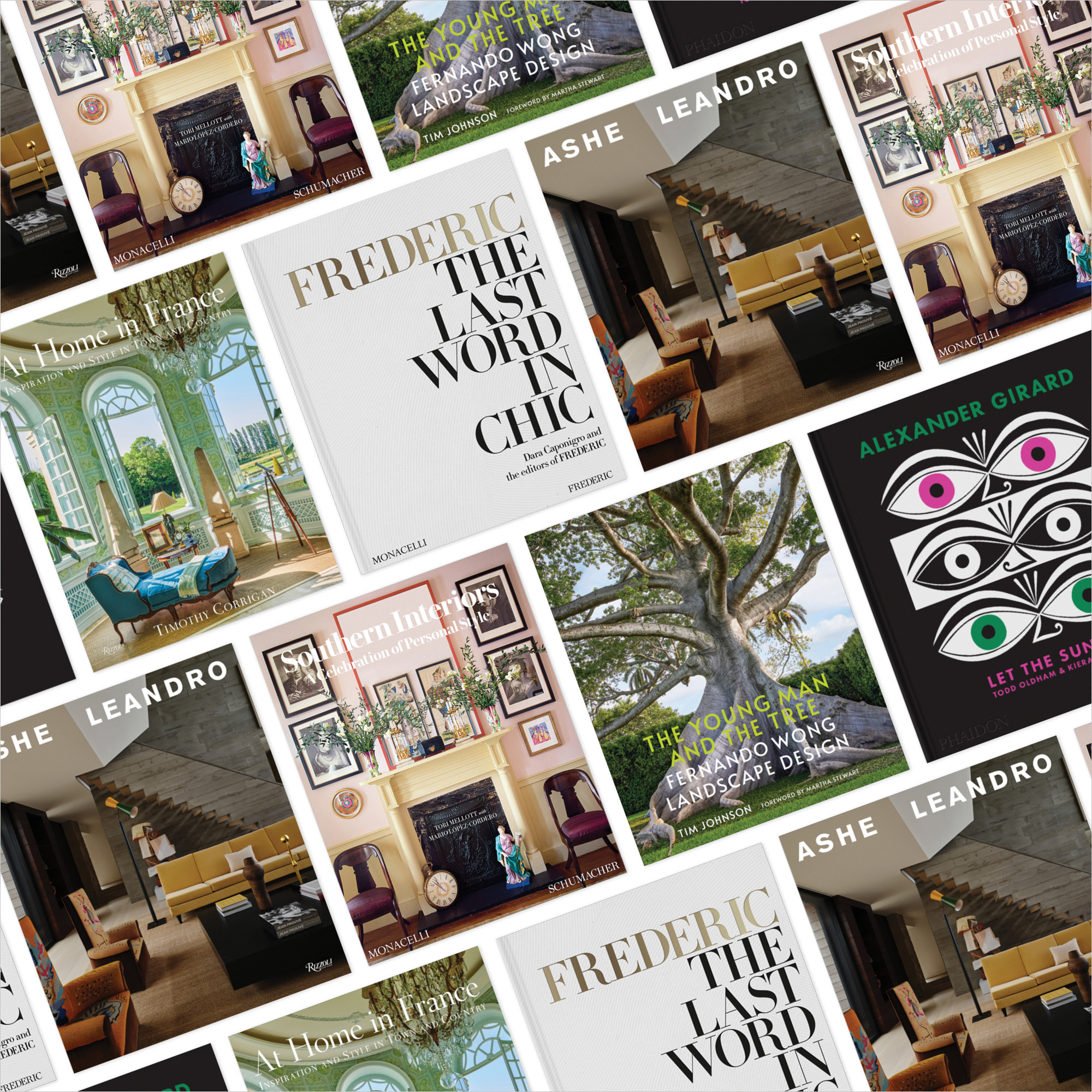

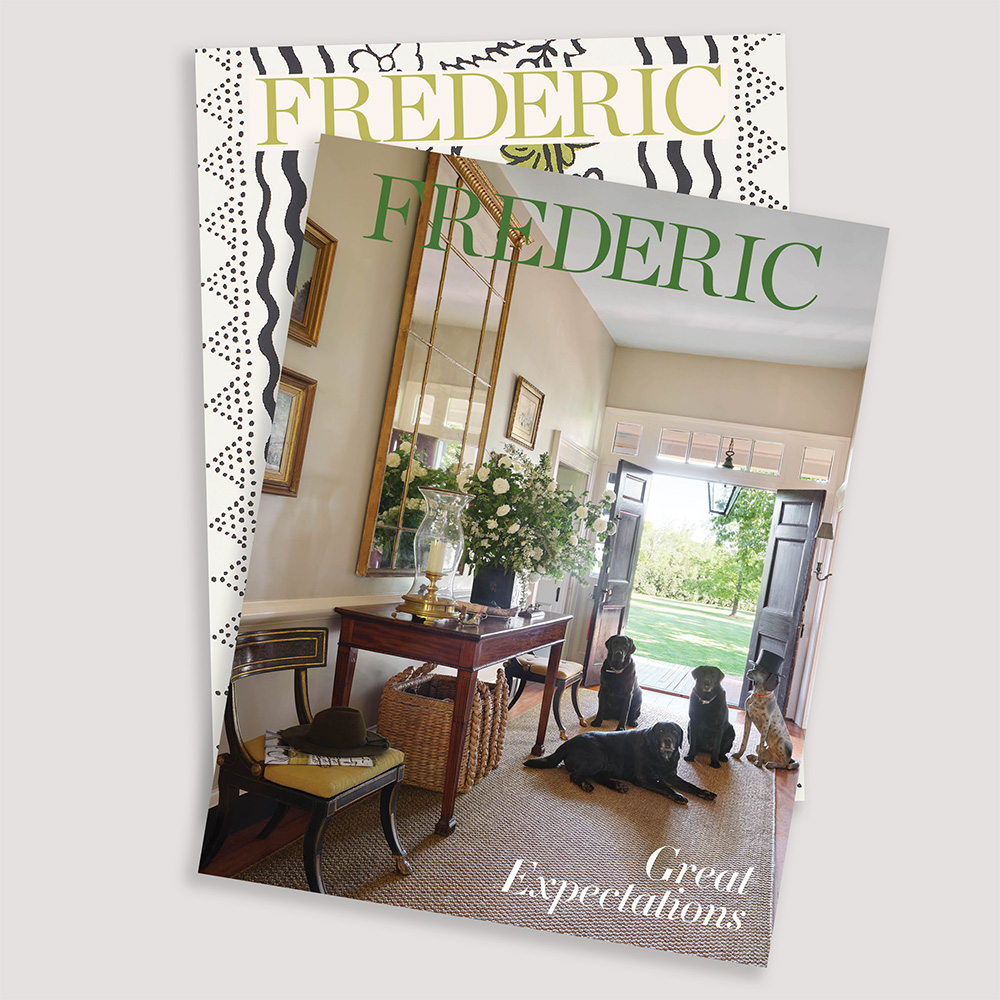

THIS ARTICLE ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN VOLUME 14 OF FREDERIC MAGAZINE. CLICK HERE TO SUBSCRIBE!